Homes for People, Not Cars (Part 2)

Picking up from my first blog post, I'd like to dive into how "homes for people" thinking translates into the design of our two current projects. Ultimately, without vehicle parking we're able to provide more value at a lower cost, which has broad implications for your health, happiness, and wellbeing.

More Nature, Less Pavement

Here is a side-by-side comparison of our Belton project and an existing houseplex in Victoria:

It's clear that if you include parking for even a modest amount of density, the room for trees and landscaping quickly vanishes. Parking stalls are typically 10'x20' plus about 50% more space for drive aisles, so roughly 300 ft2 per parking stall. They simply take a lot of space.

On Belton, our shared community commons will be a vibrant place for kids to play and people to enjoy themselves. It's a place for hosting birthday parties, reading a book, sipping a coffee, etc. In contrast, the other houseplex rear yard is largely dead space and serves a single purpose - car parking.

Better Design

Those space requirements for vehicle parking and drive aisles have big implications for building design as well. It determines where the building is situated on the lot, how many homes will fit (more on that below), and the relationship between those homes and exterior spaces.

Consider our Richmond townhouses:

Our family-orientated 3-bedroom homes have a direct connection between the living room, rear yard, and street which makes it much easier to move between these spaces.

Compare that to my current home - a typical townhouse. Here’s the view of the yard from my living room on the second floor:

While I appreciate having a yard for my kids to play in, we don't use it half as much as I'd like. It feels disconnected and distant, and I can't passively supervise my kids there. I need to be in the yard or my garage to keep an eye on them which, as a parent, is much more demanding than just letting them go out back and play independently.

Having greater flexibility in design also opens an opportunity to provide age-in-place homes with wheelchair-accessible entrances - something that's normally very difficult to provide on small multi-family housing projects like ours. This, in turn, allows us to promote intergenerational living within our projects and the broader neighbourhood - something we (as a society) have lost touch with but is critically important to healthy well-functioning communities. We're seeing increasing interest in our homes from downsizers who want to live in a residential neighbourhood and stay close to their children and grandchildren.

In short, car parking is a very restrictive design feature that affects every aspect of a home. Without parking, we can simply focus on good human-centered design.

Attainability

There are two key aspects that drive the per-unit cost of building a home - density and cost per square foot.

Density

The more homes on a property, the better costs can be spread out and the per-unit cost falls. The math is pretty simple. On our Belton project, we paid about $750,000 for the property. For six homes, that's $125,000 per home. If we only provided 3 homes instead, the land cost would be $250,000 per home - double.

The same principle applies across all fixed and semi-fixed costs including architecture fees, engineering fees, professional fees (arborist, surveyor, geotechnical, etc.), municipal fees, administrative costs, etc. Altogether, we estimate that our Belton homes would cost 36-42% more if we provided only 3 instead of 6 homes, with the exact same design.

However, if we had to provide parking on either of our projects, the number of homes would fall by at least 50%. Consider the following comparison:

A typical car-centric townhouse design.

Our 2859 Richmond Road stacked townhouse design.

By removing the car garage, we're able to make use of the ground level (the most valuable and well-connected level) and basement level for living space. This added density simply makes our homes more affordable versus a comparable home with parking.

Cost Per Square Foot

Again, some really easy math. If each square foot costs about $300, then every additional square foot will increase the overall price of a home. Therefore, to make a home more attainable, smart efficient floor plans are key. Consider our Belton three-bedroom floor plans, which are roughly 1,100 ft2:

633 Belton three-bedroom floor plan, top floor.

At $300/foot, our hard construction costs would be $330,000. If those were 1,500 ft2 floor plans, it would be $450,000. That’s an additional $120,000 at break-even cost - not including additional financing fees, contingency budget, and added risk for incurring this additional expense. So, the actual additional cost would be closer to around $150,000 per home.

An important caveat here is that cost per square foot changes over time. We're entering a high inflation environment but rising interest rates are also cooling real estate markets which, theoretically, should put downward pressure on input costs (material and labour). We won't actually know our per square foot cost until we get to construction.

There is a wide range of other expenses beyond land and construction costs that affect the price of a home, however, it is these two factors (density and cost per square foot) which determines if a home is attainably priced or not.

Community Orientated Design

This part can get a bit complex but if you look at a typical home, whether it's a single-family dwelling or townhouse, there is little to promote community and connection. Often, we step out the front door, jump into our car, and drive away with zero interaction with our neighbours. Even in apartments and condominiums, shared hallways and corridors are designed purely to move you from A to B (think awkward silent elevator rides).

A home that fosters community requires (a) creating a "sense of place" and (b) promoting "social integration" (i.e. opportunities for people to casually bump into and get to know each other).

Sense of Place

Great places feel comfortable, engaging, and safe. They generally involve a combination of natural surroundings, people, and the absence of danger. Even if you're an introvert and hate small talk, everyone wants people around them and to feel like they belong. You may love hiking in the woods, but you probably don't want to be a hermit and appreciate human connection. We're social animals and these are natural human qualities.

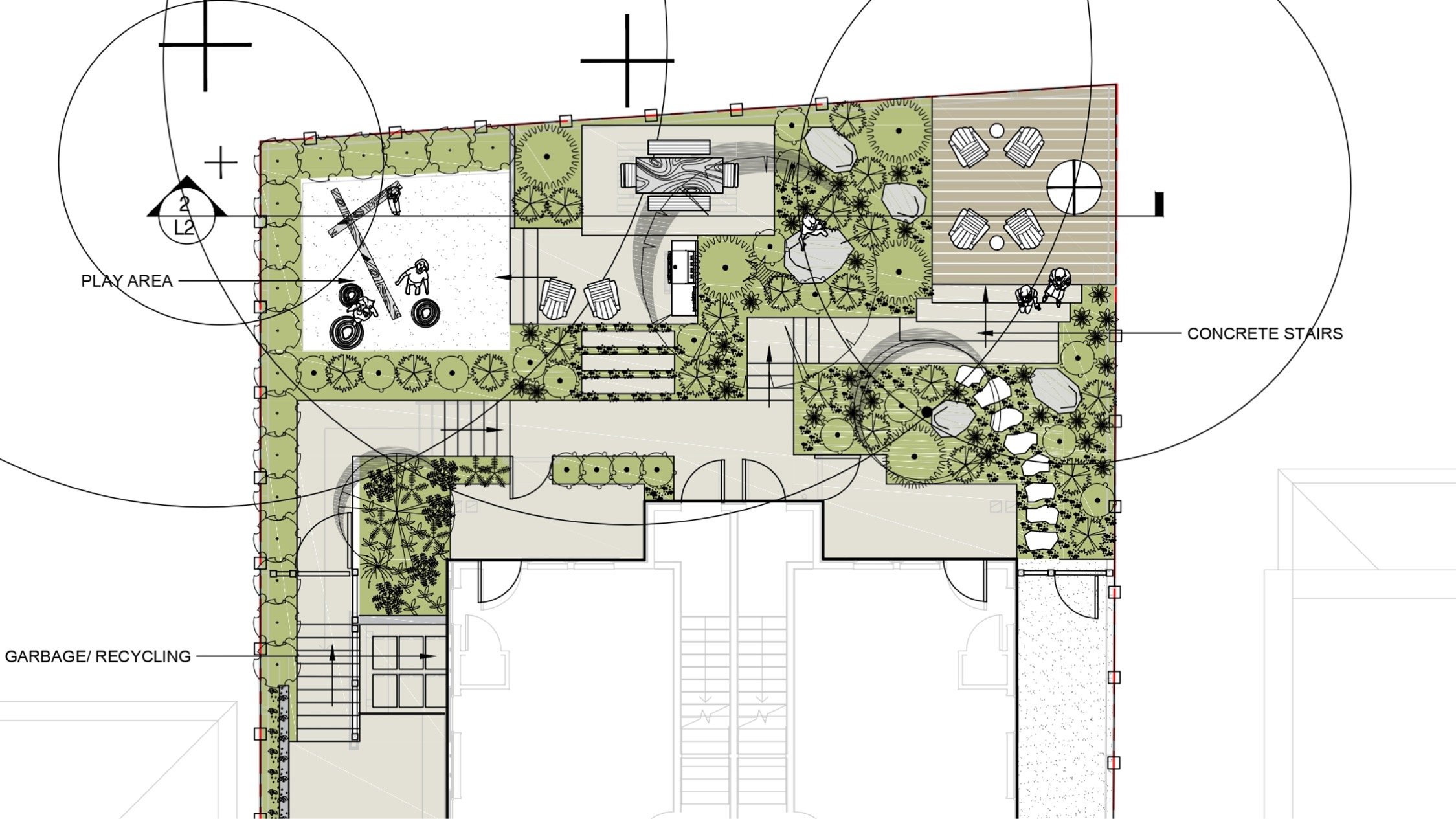

Here is the rear yard community commons on our Belton Project:

633 Belton community commons.

This is an inherently social space - a place for kids to play, for people to share a meal, or quietly read a book. It's also separated into 3 different tiers (kids’ play area, picnic table / BBQ seating, and upper deck seating), allowing people to privately enjoy the space, with the comfort of having other people around (similar to the environment created in a café or public library). It's interesting, it's meaningful, and it combines all of the elements that create a human-centric space.

Conversely, parking immediately introduces a risk that transforms how we relate to a space, especially for families with young children. A high school friend of mine lost his son because someone wasn't paying enough attention parking in his driveway. Unfortunately, this kind of tragedy is not uncommon. The way cars came to dominate urban design in the twentieth century has radically transformed our cities and streets, making much of our public realm dangerous, especially for young children. Feeling safe is a mandatory ingredient for great places.

Social Integration

Even the most beautiful space won't bring people together if it doesn't facilitate human interaction.

Social integration is a term that has a few different definitions depending on the context in which it's used, but I'm referring to the sense of belonging that comes from developing human bonds in your community, both strong and weak bonds. That is, both your close relationships (e.g. true friendships) and casual relationships - such as a neighbour you may not hang out with but you know their name, a bit about them, and you acknowledge each other kindly when you pass by.

This isn't about being excessively social or an extrovert. It's about feeling like you belong to a community, which requires at least a baseline understanding of who your neighbours are. Having many close relationships is just a stronger version of this effect.

We've tried to help foster social integration in our designs by creating frequent and comfortable opportunities for neighbours to bump into each. We've done this mostly through circulation planning - that is, how people move in and out of their homes and around the property.

Here is the frontage of our Richmond project:

2859 Richmond Allenby frontage.

The first thing to notice is that every time someone has to leave their home they have to use the sidewalk - whether they are heading to the bike garage, going for a walk, or simply taking out the trash. Compare this to a typical car-centric single-family dwelling or townhome, where someone hops into their car and drives away without any opportunity to interact with their neighbour.

Furthermore, balconies overlook the sidewalk and front steps double as seating for a casual conversation. Combine this with a park-like setting - landscaped front yards, tree-lined boulevards, beautiful architecture, and south-facing sunlight - and you have a space in which people will be chit-chatting, swap smiles, and build bonds.

Compared To…

A typical condominium has opportunities for people to bump into each other but given the number of people who live in the same building and the lack of “sense of place” communal areas, they usually feel impersonal and create little human connection. People go from their car to the elevator to their home and back, rarely seeing the same people twice in a month.

Single-family dwellings can provide a sense of place but rarely provide opportunities for people to connect, so little community is formed. This is similar to many traditional townhomes which provide limited opportunities for social integration.

Very social and extroverted people can overcome these limitations but for most, forming relationships in these environments does not come easily or naturally. Our homes help facilitate a fundamentally different relationship between neighbours and their broader community.

Final Thoughts

Most people don't realize the tremendous price they pay to own and park a vehicle - both in terms of dollars and cents but also the opportunity cost of the type of home they could have. The premise of Urban Thrive is pretty straightforward - convert the high cost of car parking into more valuable and meaningful things for those who don't need or want a car. More value, for less.

In doing so, we hope that the extraordinary benefits of living this way will inspire others to ditch the car and embrace this more healthy, happy, and sustainable lifestyle.

The community aspect of why this type of housing is so important is one of the hardest pieces to communicate. It's complex, intangible, and a few steps removed from the way most people think about housing. Research from Susan Pinker, developmental psychologist, illustrates the importance of social integration well, especially in terms of our health and happiness. If you're interested in this topic, I encourage you to watch her TED Talk "The secret to living longer may be your social life".